When the bomb detonated outside Lal Qila on November 10, 2023, security agencies assumed it was another isolated act by a lone extremist. But the investigation revealed something far darker: a 17-year-old terror pipeline rooted in a quiet university campus in Faridabad. At the center of it all? Al Falah University, a private engineering institute that, according to the National Investigation Agency (NIA), has quietly nurtured some of India’s most dangerous terror operatives since 2007.

That year, Mirza Shahab Bag, a B.Tech graduate in Electronics and Instrumentation, vanished after leaving campus. By 2008, he was linked to the Ahmedabad serial blasts, the Delhi Metro bombings, and an attempted attack on a children’s park near India Gate — a device defused just minutes before detonation. But Bag wasn’t just a lone actor. He was a recruiter, a bomb-maker, and the architect of the Indian Mujahideen’s Azamgarh module — the first terror cell in India to publicly claim responsibility for an attack via email. And he did it all while maintaining ties to Al Falah University.

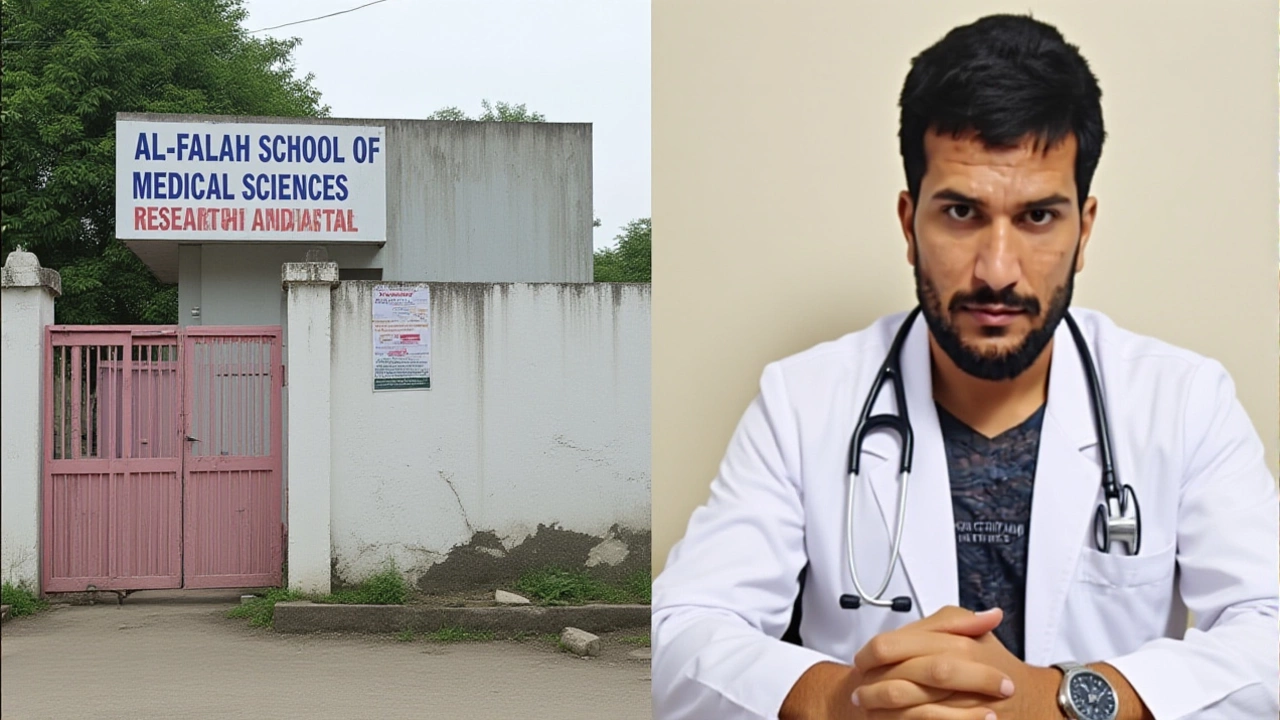

The University That Became a Terror Incubator

According to NIA documents, Bag didn’t just study at Al Falah — he radicalized there. Campus records show he frequented the mosque adjacent to campus, where Maulvi Ishaq, now in custody, allegedly received over ₹40 lakh in donations from a hardline group. That money, investigators say, funded explosives, forged documents, and travel for students who later became suicide bombers.

It’s not just Bag. The NIA has uncovered a chilling pattern: since 2007, at least seven graduates of Al Falah University have been linked to terror plots across northern India. One, Dr. Umar Nabi, blew himself up outside Lal Qila. Another, Dr. Muzammil, allegedly purchased bomb-making materials using funds siphoned from the same mosque. Both were medical graduates from a college in Jammu — not engineering students. That’s the twist: Al Falah wasn’t just producing engineers. It was producing doctors who became bombers.

The White-Collar Terror Machine

What makes this network unique is its professionalism. Unlike street-level radicals, these operatives had degrees, clean backgrounds, and access to hospitals, labs, and government systems. They weren’t hiding in caves — they were working in clinics, teaching in colleges, and filing tax returns. Investigators found that over 30 students from Al Falah and affiliated institutions were systematically targeted between 2010 and 2020. Their recruitment? A brutal psychological operation.

“They were shown videos — over and over — of Palestinian children under bombardment, of Muslims being detained in Kashmir, of mosques being demolished,” said a senior NIA officer on condition of anonymity. “Then they were told, ‘You’re the ones who can stop this.’”

Many were from middle-class families. Some had scholarships. None had criminal records. That’s what made them dangerous. They slipped through the cracks. And Al Falah’s administration, according to multiple sources, turned a blind eye.

Who’s Investigating — And What’s Next?

The scale of the probe is unprecedented. The NIA, the Enforcement Directorate (ED), Faridabad Police, the University Grants Commission (UGC), and the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) are all reviewing records from the past 15 years. That includes admission files, faculty appointments, hostel logs, and even alumni contact lists.

So far, six individuals have been arrested — including Maulvi Ishaq and two former faculty members. But the real question is: how many more are still out there?

“We’re not just looking for suspects,” said an NIA official. “We’re looking for systems. Who approved their degrees? Who signed their leave forms? Who ignored the red flags?”

The Human Cost

On campus, the mood is tense. Over 1,000 students and faculty are caught in the crossfire. Parents are writing letters to the Vice Chancellor. Some have already pulled their children out. Others are terrified of the stigma.

“My daughter is in her final year of engineering,” said Rehana Khan, a mother from Ghaziabad. “She’s not involved. But now, every employer will ask: ‘Did you go to Al Falah?’ What does that mean for her future?”

The university administration insists everything is normal. “Our accreditation is intact,” read a recent statement. “We cooperate fully with authorities.” But that’s cold comfort to families who fear their child’s diploma may now be a liability.

And then there’s the bigger question: how long did this go on? The NIA believes the university’s links to terror networks stretch back to 2007 — the same year Bag graduated. That’s 17 years. Seventeen years of silence. Seventeen years of missed warnings. And now, the reckoning.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Mirza Shahab Bag escape detection for so long?

Bag graduated in 2007, a time when India’s terror monitoring was fragmented. He used his engineering degree to blend in, moved between cities under aliases, and avoided digital footprints. His connection to Al Falah University wasn’t flagged because he was a quiet student with no prior record. Even after the 2007 Ahmedabad blasts, he wasn’t immediately linked — investigators focused on foreign operatives first.

Why are doctors being targeted for radicalization?

Doctors have access to controlled substances, medical equipment, and institutional trust. They can move freely across borders and enter secure areas without suspicion. In this case, Jammu medical graduates were chosen because they came from regions with high emotional exposure to conflict narratives. Their training made them ideal for building IEDs — they understood chemistry, timing, and pressure systems.

What’s the role of the mosque next to Al Falah University?

The mosque, managed by Maulvi Ishaq, served as a recruitment hub. Donations were funneled through religious charities, then redirected to buy bomb components, fake IDs, and travel tickets. Surveillance footage shows several suspects meeting there weekly after evening prayers. NIA has traced over ₹40 lakh in cash transactions between the mosque and known terror financiers between 2015 and 2022.

Is Al Falah University’s accreditation at risk?

Yes. Both UGC and NAAC have initiated emergency reviews. If evidence shows institutional complicity — such as falsified faculty records or ignoring known radical students — the university could lose its recognition. That would invalidate degrees issued since 2007, affecting over 1,200 alumni. Even if the administration is innocent, the association alone could trigger a collapse in student enrollment and funding.

What’s the timeline for action against the university?

NIA has 90 days to complete its forensic review of records. If findings confirm systemic negligence or support, the government could invoke the UAPA to designate the university as a ‘terrorist organization’ — a first for an educational institution in India. Legal experts say that would allow asset freezes, campus closures, and criminal charges against administrators. A decision is expected by early February 2025.

How common is this kind of terror network in Indian universities?

Not common — but not unheard of. Similar patterns were found in Jamia Millia Islamia in 2016 and Aligarh Muslim University in 2019, but never with this scale or duration. What’s unique here is the combination of medical and engineering graduates, the use of religious funding, and the 17-year span. Most terror cells last 2–3 years before being dismantled. This one survived because it operated under the radar of academic legitimacy.